“Don’t Let Your Matches Get Wet”— Nicholas Gamarello on WWII Jacket Art, Vintage Fidelity, and Designing with Memory

Nicholas Gamarello’s work lives at the crossroads of art, craft, and lived history, from restoring WWII flight jackets to shaping some of Polo Ralph Lauren’s most memorable motifs. In this conversation, he traces the family stories, music, photography, and vintage culture that formed his eye — and shares the one lesson he offers every young creative: protect the spark.

You grew up in a post-WWII, military-oriented American family. What did that world give you?

Nicholas Gamarello: My father and his brothers were aviators during the war. One never came home. It was a household where military life and its stories were present — but also motorcycles, Western films, and country music. I loved hearing my father recount his time in the Army Air Forces and his pre-war days as a loyal Indian and Harley-Davidson rider.

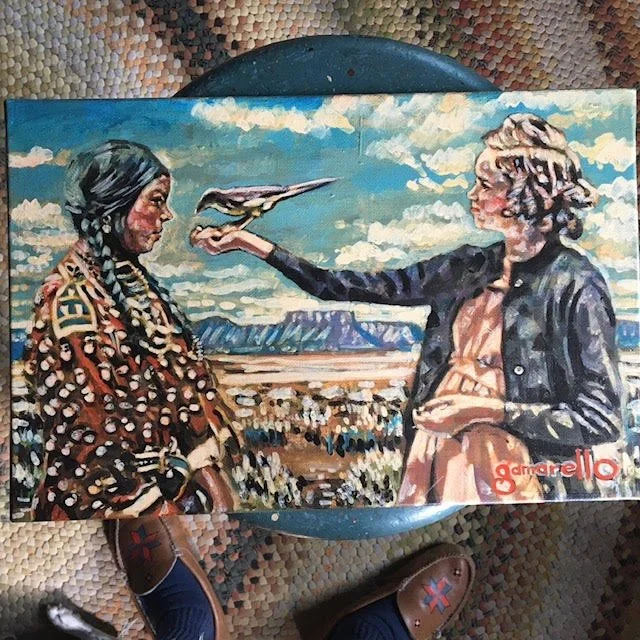

Leather Motorcycle jacket hand-painted by Nicholas Gamarello @Instagram

Some of my strongest memories are simple: Sunday “cowboy chuck wagon” breakfasts while the radio played Hank Williams or Patsy Cline. Those things plant seeds. They become your inner reference library without you even realizing it.

Before fashion became your language, you were already living in costume and imagination. What do you remember from those early years?

Nicholas: My mother had an old Singer sewing machine, and she was constantly sewing costumes for my daily imaginary adventures. I was a decent student, but school never felt like the real education. Life started when I got out of class.

Custom Singer Machines box by Nicholas Gamarello @Instagram

I remember being five years old and wanting boots like the ones Errol Flynn wore in Robin Hood — and feeling genuinely disappointed that I couldn’t find them anywhere. When I was about twelve, my parents gave me my first horse. I spent countless hours riding — some days dressed as a cowboy, other days in Native American finery. That kind of play isn’t trivial; it shapes how you see silhouettes, details, and identity.

Young Nicholas dressed like a cowboy @Instagram

Nicholas riding his horse @Instagram

Then came rock music and photography. How did that shift your direction?

Nicholas: As a teenager I got hit by two things: music and girls. I loved the Rolling Stones’ edge and their bluesy, “bad boy” image. Around the same time, I confiscated my father’s 35mm camera and fell in love with photography. For years, I was never without a camera.

In high school, I talked my way backstage at a concert — The Small Faces and Savoy Brown — and ended up taking photos. A reporter from Circus Rock Magazine asked for my film because their photographer didn’t show. Ron Wood overheard and advised me not to give up my negatives — to keep control and sell the photos properly. I did, and that turned into a job as an assistant photographer. I got access to concerts and scenes that felt like heaven — and without realizing it, I was also discovering fashion.

Greenwich Village in that era was a living classroom. What did working in vintage teach you?

Nicholas: Hanging around the Fillmore East and the Village, I became friendly with Freddy Billingsley, who owned a boutique called Limbo on St. Mark’s Place. That shop was a slice of heaven: genuine vintage clothing, military surplus, and contemporary pieces — including denim. Freddy became a mentor and taught me categories of clothing. I also crossed paths with places like Gentleman John’s and Granny Takes A Trip.

I couldn’t afford most of what I helped sell, but through hand-me-downs and custom pieces that didn’t fit customers, I started building my own look. My artistic skills also became useful: I learned to sketch detailed fashion drawings to help cobblers back in England — and to help customers visualize what they were asking for before committing time and money.

“Studying the art of flying jackets is like studying glyphs: a whole life told in symbols.”

Your name is closely tied to WWII aviation jackets. What fascinates you about them — beyond the surface?

Nicholas: I wore my father’s WWII flying jackets, his pre-war motorcycle gear, and his vintage Western wear — which motorcyclists wore a lot at the time. Vintage shops were everywhere, and you could find old flight jackets inexpensively. I’d buy them, wear them, repair them. I became efficient at restoring them.

But the deeper fascination is that a flight jacket can tell a life story. The patches show branch of service, theater of combat, squadron identity. The artwork often reflects a pilot’s experience — missions, victories, personal symbols. It’s like studying a form of glyphs: compressed biography through graphic language.

Leather A2 Flight Jacket Hand-painted by Nicholas Gamarello for SUPREME x Schott Collaboration

That knowledge, coupled with actual relics and restoration skill, became a sideline business. I’d sell pieces to fund better ones, and my work began to circulate. Early customers included Willis & Geiger Sportswear, and for years Cockpit/Avirex carried my specialty jacket art.

You trained as a fine artist — then built a commercial career. What did that transition look like?

Nicholas: After high school I went to the School of Visual Arts in New York City and studied painting. I learned from the masters — Rembrandt, Vermeer, Caravaggio — and I loved the discipline of tonal painting, even if the subject matter didn’t always feel like my world.

Painting of Doug Bihlmaier, longtime vintage clothing buyer for Ralph Lauren, by Nicholas Gamarello

Nicholas Gamarello painting

My lifelong favorites are artists like J.C. Leyendecker, William R. Leigh, Alfred J. Munnings, Charles M. Russell, John Singer Sargent, and William Orpen. Their work still hits me emotionally.

After graduation, I did commercial illustration — magazine art, covers, book jackets, even record posters. I eventually needed steadier work and became an Assistant Designer at Macy’s Parade Studios, designing parade balloons and floats and technical drawings for events. I met incredible people — including Jim Henson, when we worked on a project connected to Fraggle Rock. And at night, I still painted, illustrated, and worked on leather jackets.

“Ralph didn’t need me to create chinos and polo shirts — he needed editorial, unique concepts across the board.”

How did Polo Ralph Lauren enter the story — and what was your role once you arrived?

Nicholas: I was featured in news articles, including one in The New York Times. Ralph Lauren saw the stories and liked what he saw. We started communicating — letters and phone calls — and eventually he visited my home studio with his family.

When I met with Ralph and his partner Peter Strom, I was asked if I was a Polo customer. I said no — not out of disrespect, but because sometimes I’d see a piece from across the street, cross over to look closer, and feel disappointed by a fabric choice or a buckle detail. That honesty became the point: they hired me.

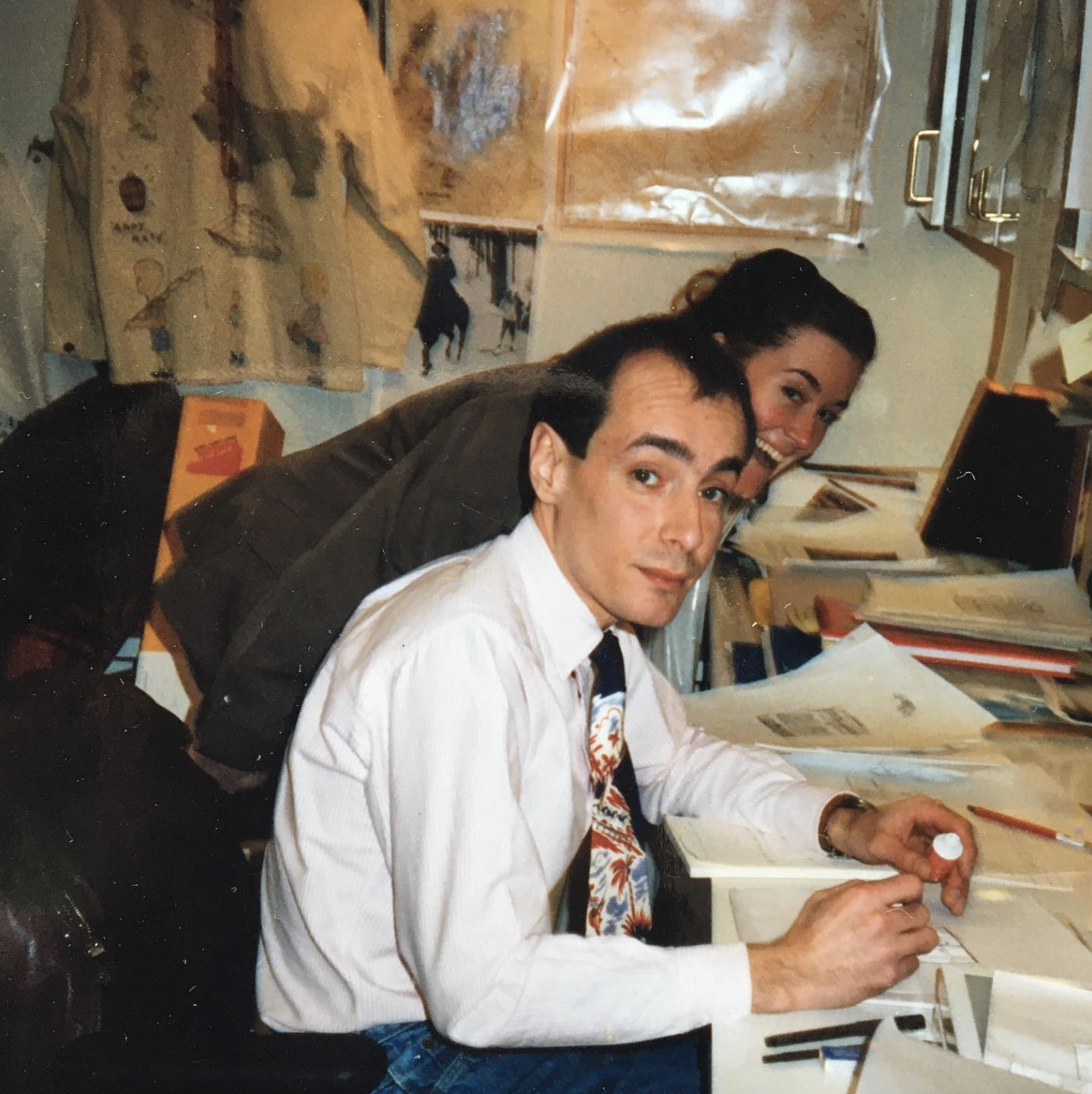

Nicholas and his dearest friend the Fashion Designer Victoria Bailey at Ralph Lauren @Instagram

I came in thinking I’d try it for a few months. I stayed about thirteen years. Ralph gave me a unique position with freedom to move between divisions — men’s, women’s, home — creating editorial concepts, graphics, sweaters, outerwear, accessories. The work wasn’t the hardest part. The hardest part was navigating fashion-industry personalities. But once I got going, people welcomed what I brought.

What work from your Polo years still feels most “you”?

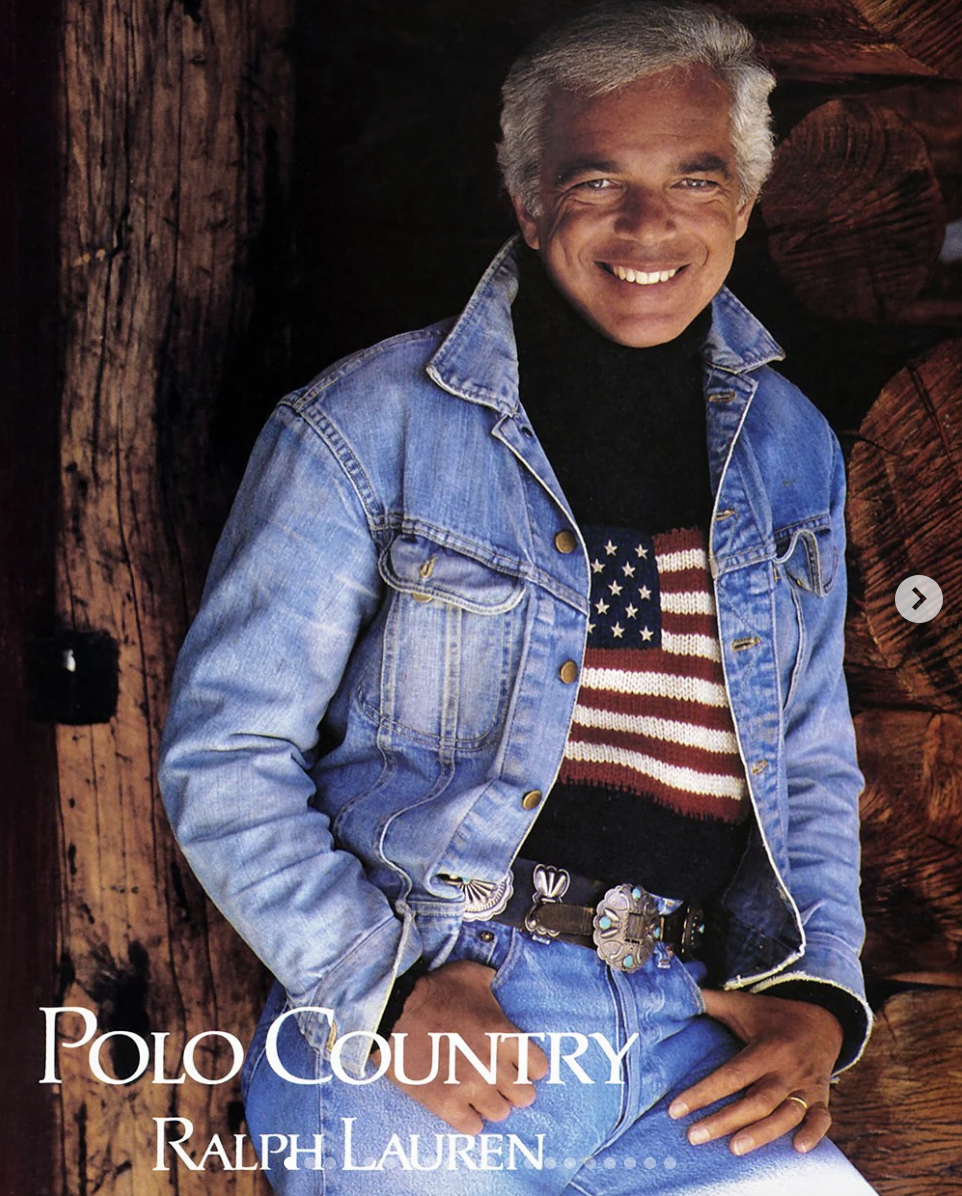

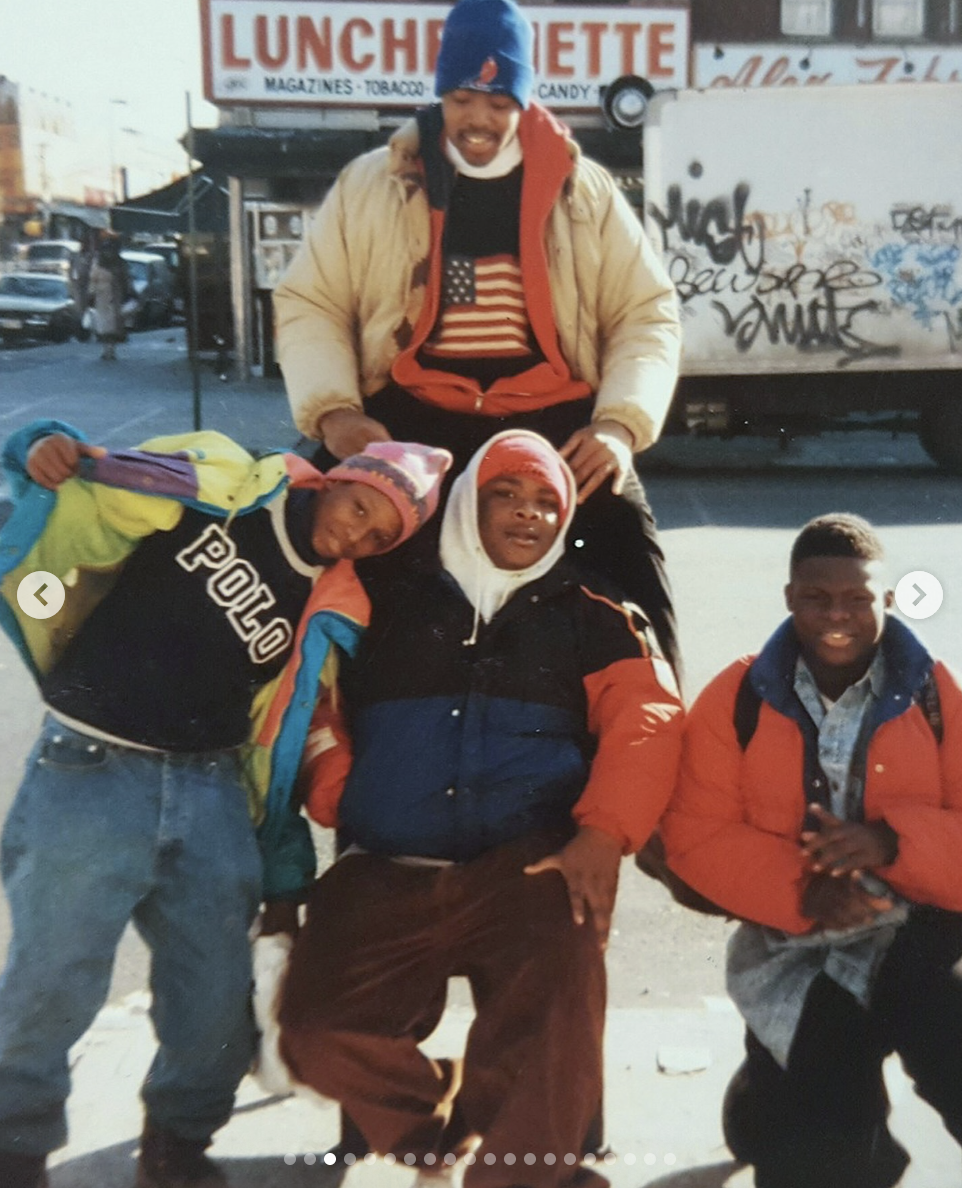

Nicholas: I loved creating special “trophy” Southwest leather garments — things like Native American–inspired pictographs on buckskin. And I remember the American flag sweater. That concept came from the flag worn on the backs of jackets by Flying Tigers pilots in China.

Ralph Lauren wearing the American Flag Sweater @ThePoloArchive

American Flag Sweater @ThePoloArchive

When I first presented it, Ralph’s brother Jerry thought it was a dumb idea. Ralph said, essentially, let him do it — if the sample isn’t great, we drop it. The sample looked fantastic. It became a hit. Those were the days when there was room for expression — before the company went public and corporate.

After Polo, what kind of creative life did you build?

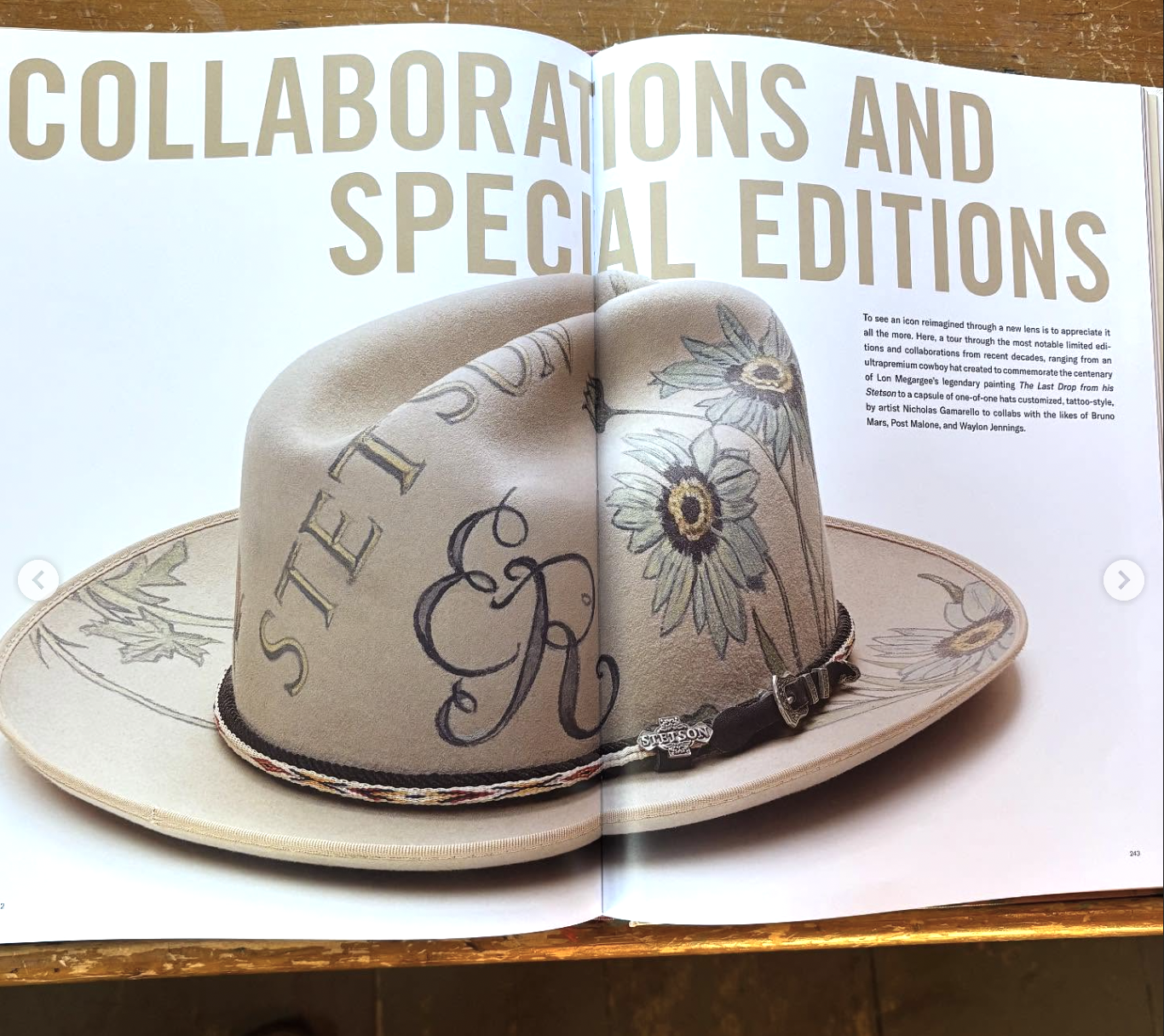

Nicholas: I worked with John B. Stetson Co., Marithé François Girbaud, Ghurka, and many freelance commissions. Most work comes by word of mouth. I don’t advertise. My only social outlet now is Instagram.

Nicholas Gamarello’s work for Stetson

You tell a story about an “imaginary book of matches.” What does it mean — and what advice do you give to young creatives and collectors?

Nicholas: My father once took me to a toy shop and told me to pick a hand-painted soldier figurine. I chose one, and he asked why — because its leg was broken. I told him I liked his face best.

Later he said: inside everyone is an imaginary book of matches. When you encounter someone, something, or someplace truly special, one match ignites. You have to listen to that. It’s your soul telling you who you are. And when people stop paying attention, those matches get wet and moldy — and they don’t ignite anymore.

“My advice is: never let your matches get wet.”

For beginners: buy only what you truly love — ideally what you can wear. Don’t start by chasing profit; it rarely works that way. Buy what you can afford and enjoy. Let items speak to you. Be passionate in your acquisitions.

Over time I built my own reference archive. My work is never meant to trick anyone — it often looks like it’s from another age, but I always sign it. If it keeps a memory alive — a personality, a period — that matters. Life is a journey. Proceed at your own pace, enjoy the trip, and make each project your own Fabergé egg.

Many thanks to Nicholas Gamarello for taking the time to answer our questions.

Follow Nicholas on his Instagram