The Age of the Irreproducible

Why custom vintage is not a trend but a cultural correction

Heritage menswear has always been about preservation. For two decades, collectors chased original M-65 jackets, deadstock denim, naval pea coats, fisherman sweaters with untouched collars. The value of a garment lay in its fidelity to the past. Condition mattered. Authenticity meant restraint. To own was to conserve.

But culture does not stand still. In 2026, something subtle is shifting inside the heritage community itself. The archive is no longer only being preserved. It is being entered.

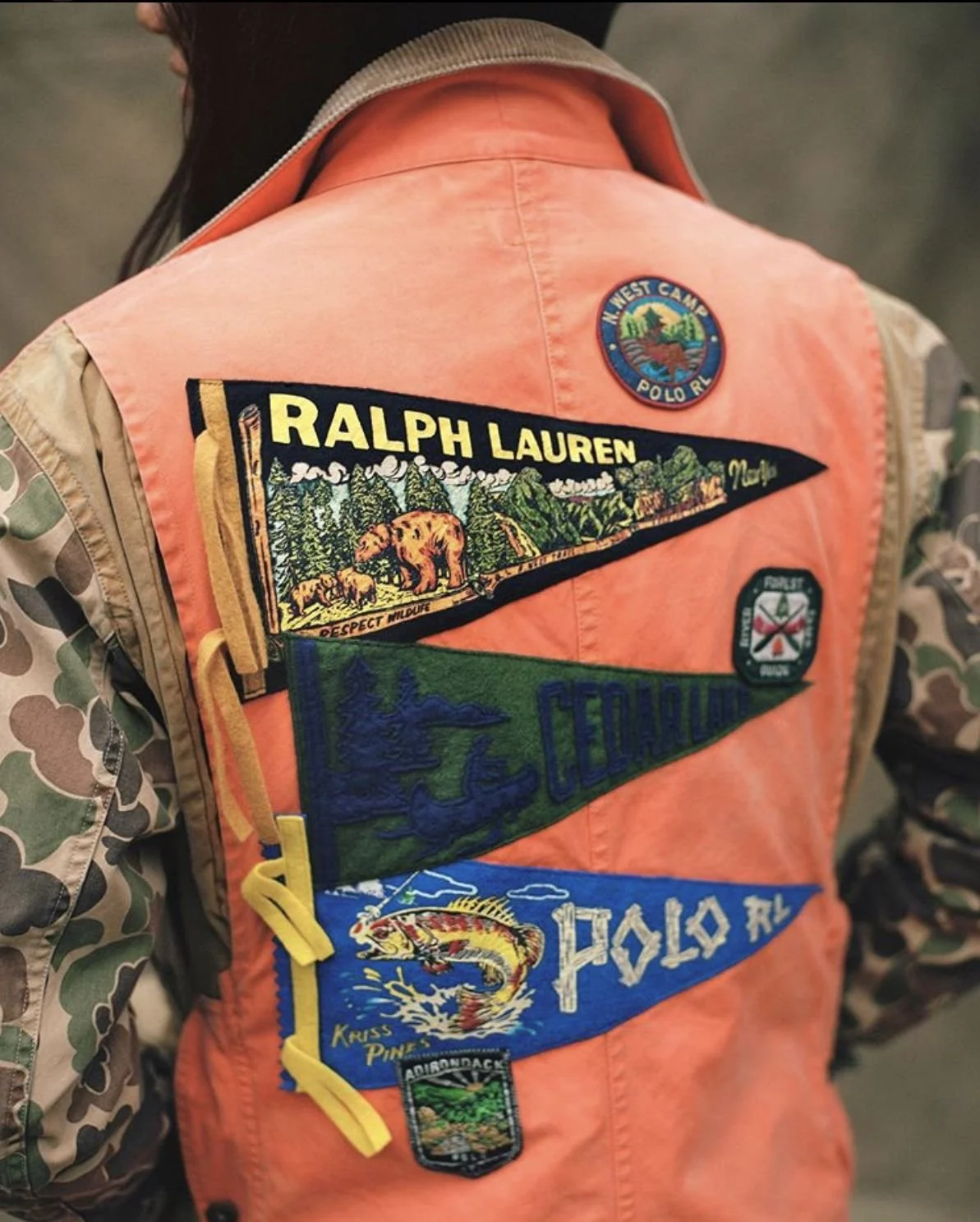

Custom jacket with Ralph Lauren pennants, Jaclyn Goldberg

Custom Pennant jacket, Pinterest

Vintage garments are being cut, layered, reassembled. A military liner becomes the foundation of a chore coat. Two sweaters merge into one new knit architecture. A discontinued hiking bag is dismantled and reconstructed from fragments of its own lineage. The intervention is deliberate, not decorative. The result is singular, not scalable.

This is not destruction of heritage: it is participation in it.

When infinite imagery produces emotional fatigue

The timing is not accidental. Artificial intelligence now generates fashion imagery, product concepts, and styling proposals in seconds. Digital feeds compress time until trends feel simultaneous. Resale platforms have made once-rare archive pieces globally searchable. The M-65, the varsity jacket, the fisherman sweater, icons of heritage, are no longer discoveries. They are categories.

The paradox of abundance is sameness.

When everything is accessible, nothing feels rare. When every silhouette is algorithmically optimized, garments lose friction. They become images before they become objects.

The German cultural theorist Walter Benjamin wrote in 1936 about the “aura” of an artwork. The presence that mechanical reproduction erodes. Today, mechanical reproduction has evolved into algorithmic reproduction. We are surrounded by infinite simulations of style.

And so aura migrates.

It no longer resides solely in untouched archive pieces catalogued online. It begins to reside in the altered object, the one that cannot be meaningfully duplicated because its value lies in physical intervention.

Japan and the cultural permission to repair

To understand why reconstruction feels coherent rather than chaotic, one must look toward Japan.

Long before Western fashion romanticized visible mending, Japanese textile culture practiced it out of necessity. Boro garments layered, patched indigo workwear from rural communities accumulated history through repair. Sashiko stitching reinforced weakness while leaving the act of repair visible. Cloth was not sacred because it was pristine. It was sacred because it endured.

Canadian Sweater before customization, Asaka Fushimi

Custom Canadian Sweater, Asaka Fushimi

The exhibition Boro: Threads of Life at Japan Society in New York formalized this understanding for Western audiences. The garments were not presented as trend objects, but as lived material memory.

Contemporary Japanese designers internalized that philosophy and translated it into menswear. Brands such as Kapital and Visvim absorbed American military and workwear references, then reconstructed them through meticulous patchwork and layered fabrication. As W. David Marx argues in Ametora: How Japan Saved American Style, Japan did not merely replicate American heritage: it refined and reinterpreted it.

Today’s custom vintage layering echoes that lineage. It does not treat heritage garments as relics behind glass. It treats them as living material.

From preservation to authorship

This is where the cultural shift becomes meaningful.

The 2010s trained men to be archivists. Knowledge of Talon zippers, selvedge IDs, contract numbers, and fabric mills became markers of literacy. Ownership was proof of connoisseurship.

But as the resale market professionalized. The hierarchy flattened. Rare became searchable. Discovery became frictionless.

What follows saturation is intervention.

Jay-Z wearing custom sweater by Asaka Fushimi

To alter a vintage garment requires confidence. It requires knowledge of its construction before modification. The person who reconstructs a field jacket understands its seam logic. The one who merges knit panels respects gauge and weight. This is not amateurism. It is advanced literacy.

The wearer transitions from collector to author. He does not erase history. He writes himself into it.

Slowness as cultural resistance

There is also a temporal dimension.

AI accelerates visual culture. Trend cycles shorten. Consumption becomes reflexive.

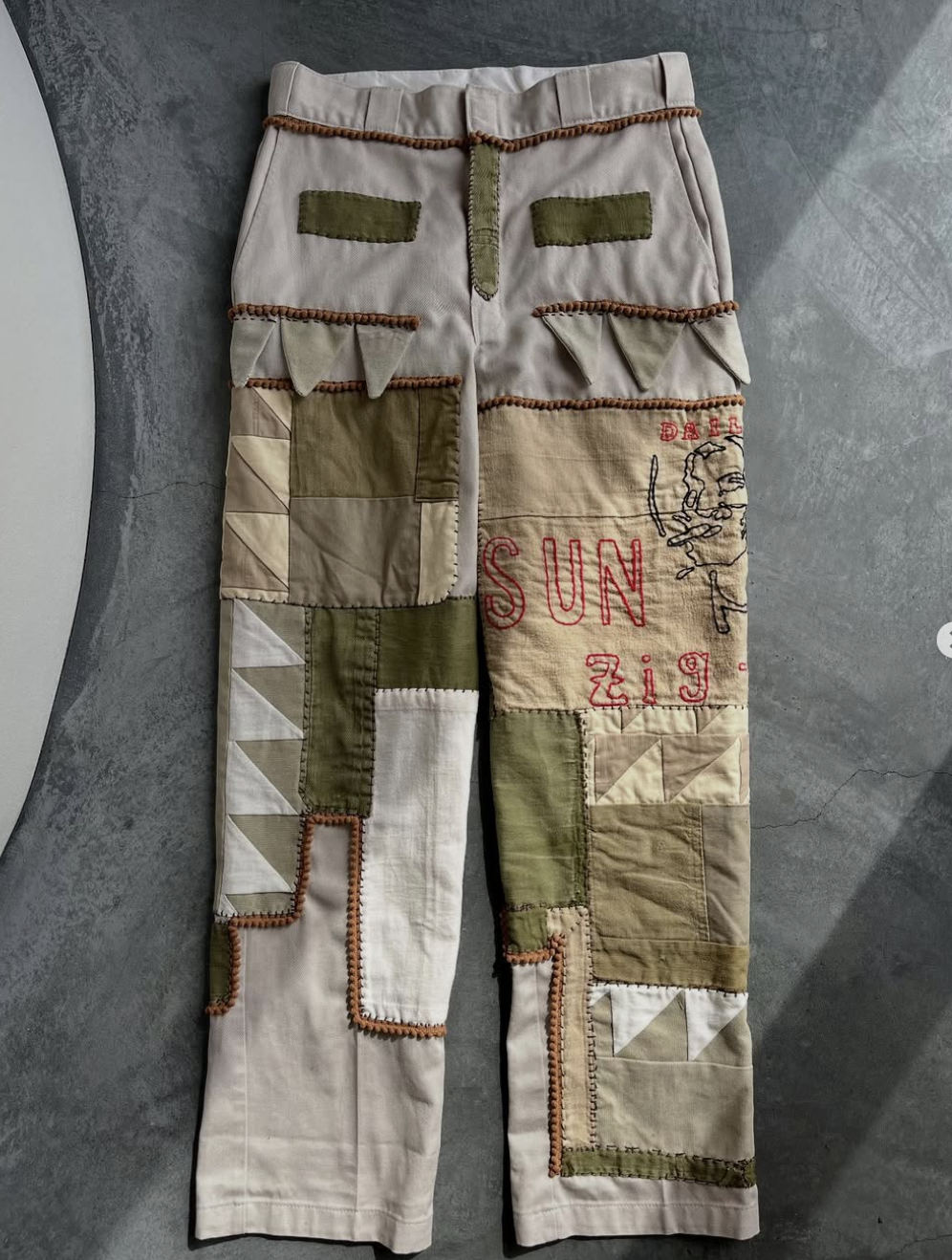

Vintage Custom Levi’s, Rarahandmadestore

Custom & patched Dickies pants, Rarahandmadestore

Reconstructing vintage is slow. It is tactile. It involves risk. Once cut, the garment cannot return to its previous state. That irreversibility restores gravity to clothing.

In this sense, custom vintage is not an aesthetic rebellion but a temporal one. It resists speed by demanding attention. It rejects infinite scroll by insisting on physical presence.

Heritage menswear has always valued durability and permanence. Reconstruction extends that value system rather than contradicting it. It allows the garment to live again, not as reproduction, but as evolution.

Sustainability without exhibitionism

Corporate sustainability often arrives accompanied by messaging. Neutral tones, ethical positioning, curated narratives of responsibility.

Reconstructed vintage operates differently. It extends life without proclamation. It preserves material through transformation. The visible seam is not branding. It is evidence.

Custom Big Ben Shore Jacket, Rarahandmadestore

Custom French Workwear Jacket, Rarahandmadestore

In a period where sustainability risks becoming aesthetic minimalism, reconstruction reintroduces texture, contrast, and narrative density. It feels less like marketing and more like continuation.

The future of heritage

Heritage clothing has always been about story, about naval labor, agricultural work, military service, exploration. What is emerging now is a second chapter in that storytelling.

The most compelling garments of the coming years will not be those frozen in archival perfection. They will be those that carry two timelines: the original moment of production and the contemporary moment of intervention.

Heritage does not weaken when it is respectfully altered. It deepens.

In an era of artificial generation and digital sameness, the most powerful garment will be the one that cannot be reproduced, not because it is rare in database terms, but because it has been physically rewritten.

The age of the irreproducible is not the end of heritage. It is its next evolution.

Go Further

Our friend Wouter Munnichs from Long John also wrote an interesting article about Customized Denim Jackets as a form of Art.

Instagram of Rarahandmadestore (everything is sold out so fast!)

Instagram of Asaka Fushimi (follow her drops)

Instagram of Jaclyn Goldberg (wonderful vintage workwear clothing with great rework)

One book to understand deeper Japan culture around Americana: Ametora