The Boys Who Watched the Sea

In the early years of the First World War, Britain feared the edge of its own geography. The threat did not only live in trenches across the Channel. It lived in the dark line where sea met sky, in the possibility of German ships slipping toward the coast, and in the new terror of air raids arriving without warning. Before radar, before modern detection, the country depended on observation. It depended on people who could look, recognize, and report.

And among those watchers were boys.

The Sea Scouts and the logic of an island nation

Sea Scouts, @IWM

The Sea Scouts were the maritime branch of the Scouting Movement created by Robert Baden-Powell. Launched in Britain in 1910, Sea Scouting was shaped by a national truth that required no explanation to anyone living on those shores: Britain was an island, and the navy was not only a military force but a cultural backbone. In coastal towns and port cities, boys were trained in seamanship, signalling, knots, navigation, and lifesaving. These were practical skills in peacetime. In wartime, they became a kind of readiness.

When youth became part of coastal defense

Sea Scout, @IWM

Sea Scout standing, @IWM

When war broke out in 1914, invasion anxiety spread quickly. The coastline suddenly felt like a front line, and the sky itself became suspect as German Zeppelins began to redefine what “attack” could mean. In that climate, Sea Scouts were integrated into a civilian coast-watching network. Their work was quiet and repetitive, built on long stretches of attention rather than moments of action. They scanned the water for suspicious movement. They noted what did not belong. They observed aircraft and reported patterns. They carried messages between points and supported coastguard activity where they could. They were not combatants, but they were trusted with the discipline of vigilance.

The coast-watching badge and what it meant

A small badge placed below the neck on certain Sea Scout jumpers marked coast-watching duty. It was not decoration in the way we think of patches today, as styling or self-expression. It was recognition, and it was proof. It signified hours completed, service rendered, and participation in a national effort that pulled civilians into the mechanics of defense. For a teenager, that badge was a public statement: you had stood watch, you had been counted, you had done something that mattered.

The Sea Scout jumper as wartime knitwear

Sea Scouts Jumper, @IWM

Sea Scouts Jumper side, @IWM

Sea Scout Jumper Sleeve, @IWM

The most striking object left behind by this story is the jumper itself. The Sea Scout jumper worn during WWI borrowed its visual language from the Royal Navy, but it translated that language into knitwear. Heavy wool made sense for the job. You could stand on an exposed coastline and survive wind, damp, and cold without the stiffness of tailored cloth. The sailor collar framed the shoulders with a naval silhouette. The chest lettering, “SEA SCOUTS,” turned the body into a sign. Badges accumulated on sleeves and chest as a record of skill and duty, stitched by hand, slightly irregular, deeply personal.

The pictured garment and the truth of wear

Look closely at the knitwear shown here and you can read its life. This is not a uniform preserved in perfect condition for display; it is a garment that worked. The wool looks dense and weather-ready (the same kind we found on first racing jerseys of Harley-Davidson or American Football Clothing in the 20s) . The shoulder construction suggests reinforcement for strain and movement. The badges are not factory-perfect; they sit like evidence, applied with the intent of permanence. The whole piece carries the unmistakable presence of use, the way real clothing holds on to the body’s habits even after the body is gone.

Sea Scouts Jumper close-up, @IWM

Why this uniform matters to menswear history

From a menswear perspective, the Sea Scout jumper is more than a youth uniform. It is an early civilian adoption of naval codes, and it arrives before maritime style becomes romantic, commercial, or stylized by fashion. It belongs to the same lineage that later produces the fisherman sweater, the naval-inspired sportswear of the interwar years, and the maritime workwear references that keep resurfacing in Americana. It shows how military aesthetics do not only trickle down through adult uniforms, but also through youth movements where discipline and identity are literally worn.

The militarization of childhood, quietly stitched in wool

Young Sea Scout watching the sea, @IWM

The First World War blurred boundaries everywhere, including the boundary between childhood and national responsibility. Sea Scouts did not carry weapons, but they absorbed the language of service and structure. Uniforms turned boys into symbols of readiness. Knitwear became part of that transformation, not as softness, but as endurance. A wool jumper can look humble, but in wartime it becomes a tool: it keeps the body warm enough to stand still and watch, and it communicates belonging to a system larger than oneself.

The legacy Sea Scouts carried after 1918

By the end of the war, Scouting had cemented its place in British society as something more than a healthy outdoor movement. It had proven usefulness. It had produced visible service. Many Scouts would later enlist when they came of age, carrying forward habits learned in Sea Scouting: observation, signalling, discipline, responsibility. The movement’s postwar legitimacy was not built only on ideals, but on the memory of what those boys had done when the coastline became a place of fear.

Sea Scouts during WWI, @IWM

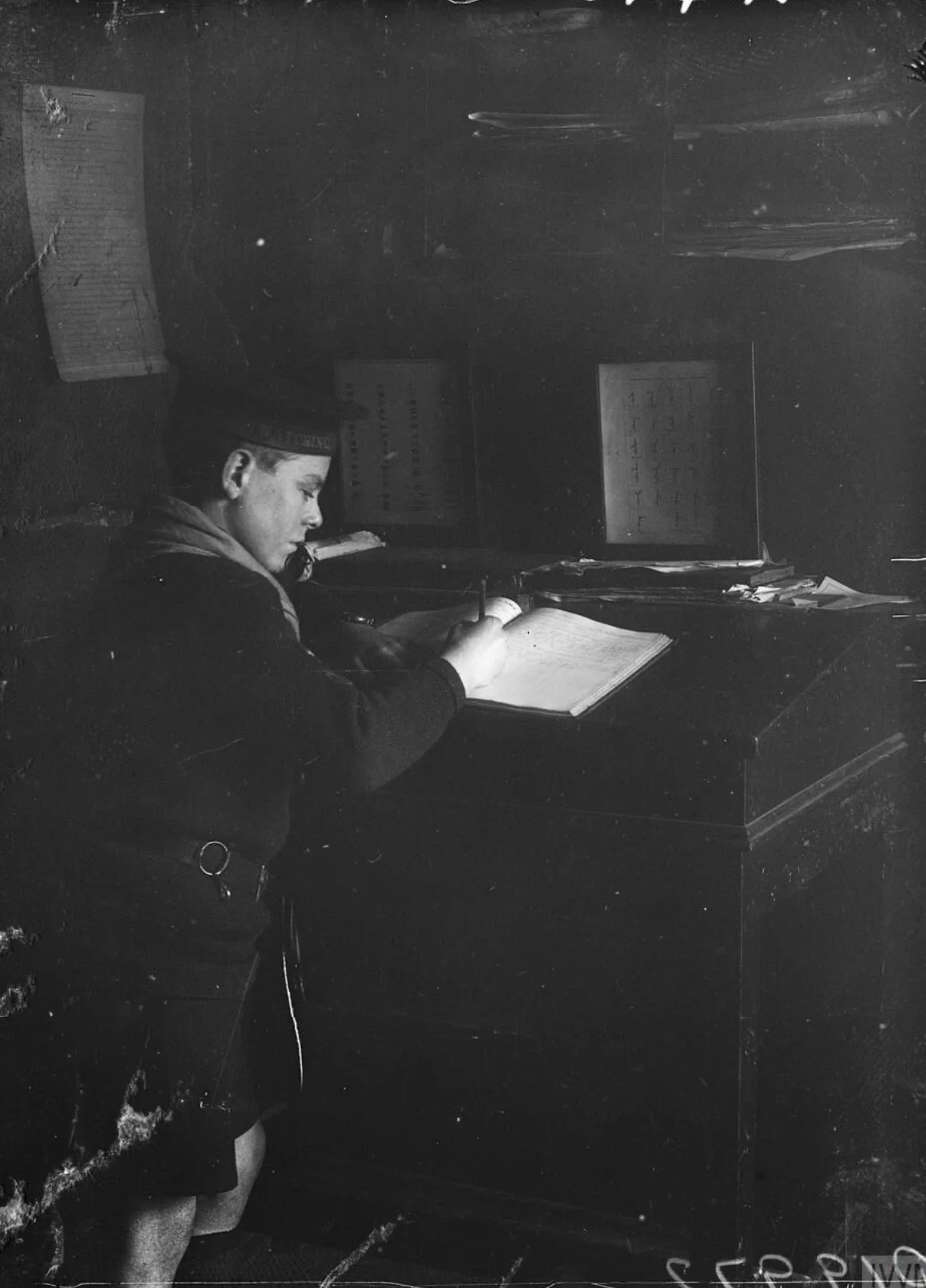

Sea Scout writing during his service, @IWM

Boys, wind, and the horizon

Along Britain’s shores more than a century ago, Sea Scouts stood in heavy wool with their eyes fixed on the sea. Their task was simple and relentless. They watched for what might come. They watched because the country asked them to. In that act of watching, a youth movement became part of wartime infrastructure, and a knitted jumper became a historical document. Knitwear, here, is not just heritage. It is witness.

If you were captivated by the story of the Sea Scouts, our Anthology of Militaria expands that world ;exploring the uniforms, objects, and overlooked details that shaped military and civilian dress.